An enormous volume of racist, homophobic, sexist and other discriminatory abuse of Premier League footballers and clubs on social media has been revealed in new research for the game’s anti-discrimination organisation, Kick It Out.

The search of Twitter, Facebook, supporters’ forums and blogs, using key abusive terms with players’ and club names, refined to identify direct abuse, found 134,400 discriminatory posts this season, from August 2014 to last month.

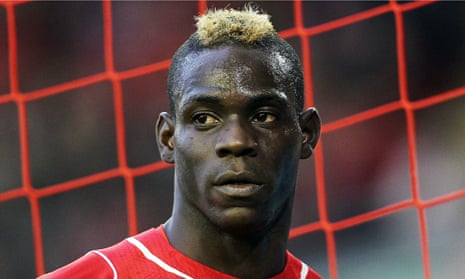

The research has also highlighted the huge number of abusive posts received by some individual black players, finding that Mario Balotelli, of Liverpool, was sent more than 8,000 discriminatory posts on social media, of which more than half were racist. Danny Welbeck, who moved from Manchester United to Arsenal in September, received 1,700 abusive posts, exactly half involving racism. Daniel Sturridge was sent about 1,600 discriminatory posts, more than 60% abusing him on the grounds of sexual orientation.

The research, conducted by Tempero, the social media management agency, and Brandwatch, a social intelligence and analytics company, found that 88% of those posting the abusive messages were on Twitter, 8% on Facebook, 3% on fans’ forums and 1% on blogs. The five clubs, in order, receiving the most discriminatory abuse were Chelsea, who were the subject of 20,000 messages; Liverpool, 19,000; Arsenal, 12,000; Manchester United and Manchester City, with 11,000 each. The research also highlighted the matches that generated the most discriminatory messages, which mostly involved those clubs.

The finding, that more than 134,000 discriminatory messages were sent in the first seven months of this season, potentially amounting to hate crime, has prompted Kick It Out to call for the football authorities, internet companies and police to form an expert panel that can collectively consider taking action.

Roisin Wood, Kick It Out’s chief executive, said the organisation is not satisfied with the response from the police to even the relatively small number, only 113 last season, which it referred to them from reports it received. Kick It Out has said it only received responses from the individual forces in 31 cases. Only nine reached a conclusion in which the offender was identified and action taken; one led to a prosecution and in two the young people involved agreed to undertake an education session to deter them repeating the discriminatory abuse. Wood argues that the internet companies also need to deal with abuse more strongly.

“This is a huge amount of awful abuse,” Wood said. “A lot of it is vile, and something needs to be done. We are really frustrated by the police response but we also understand that they cannot investigate all of this. We have to take it seriously and that is why we are inviting the relevant bodies and authorities to work together to find ways of addressing it.”

Superintendent Paul Giannasi, of the National Police Chiefs’ Council hate-crime working group, said he would welcome an invitation to be involved in the expert group addressing social media abuse in football. The Premier League said its clubs do report discriminatory abuse received by their players to relevant authorities and social media sites, and that the league would welcome further discussion on the action that can be taken.

The Football Association said that as its disciplinary jurisdiction extends only to “participants” – players, club staff and officials, not supporters – it is not currently considering being involved in the proposed expert panel. The view within the FA is understood to be that if posts on social media are racist, homophobic and could constitute hate crime, the police are the appropriate body to deal with it.

Kick It Out’s reporting officer, Anna Jönsson, refers all reported incidents of alleged racist abuse to the police’s official hate crime reporting website, True Vision, which automatically passes them to police forces local to the person complaining.

In the past year, only 4,169 hate-crime incidents of all kinds – not restricted to social media – were reported to the police via the True Vision website, a fraction of the total this research restricted to football has found. Giannasi said all are referred to local forces, who have a policy of recording incidents. Policing principles are that a response has to be “proportionate” to an alleged crime and social media abuse is often considered difficult, given the anonymity that users usually adopt. The police do not nationally produce figures on forces’ response to alleged internet hate crimes reported via True Vision.

“The police do not routinely trawl the internet for hate material,” Gianassi said, “but we are proactive in trying to find solutions to the problem. We work with industry partners and others to try to find solutions that balance the right to free speech with the need to protect individuals from targeted abuse.”

Twitter believes it features highly on public research into social media abuse because, unlike Facebook, most of its interactions are public. Dick Costolo, Twitter’s chief executive, was in February revealed to have told staff the company “suck at dealing with abuse and trolls” and has promised to strengthen its approach.

A spokesperson told the Guardian: “Abuse is against our rules. We have recently made it easier to report, allowed people to report on behalf of others, and tripled the size of the team that handles these reports. There is still more to be done, by us and the industry as a whole, but we are working very hard to stop online abuse when it happens on our platform.”

Wood said Kick It Out recognises the difficulties the police and internet companies have in dealing with such an extraordinary level of abuse, and said she hoped the expert panel may find “creative” ways to address its prevalence in football.

“We do not want to criminalise young people and we offer education to them but people have to realise there are consequences. We recognise the police cannot investigate all of this; we may need creative solutions as well, such as a broader football education campaign,” she said.